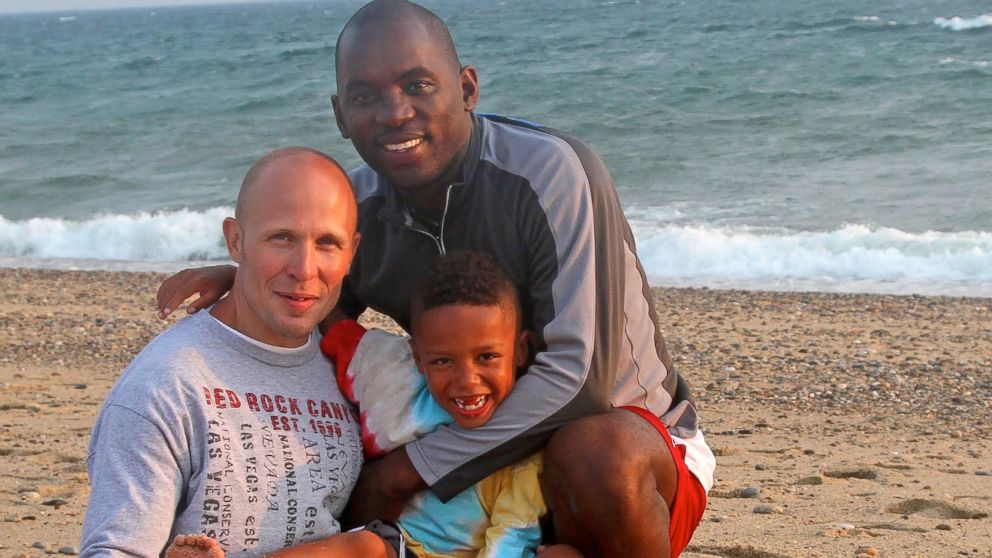

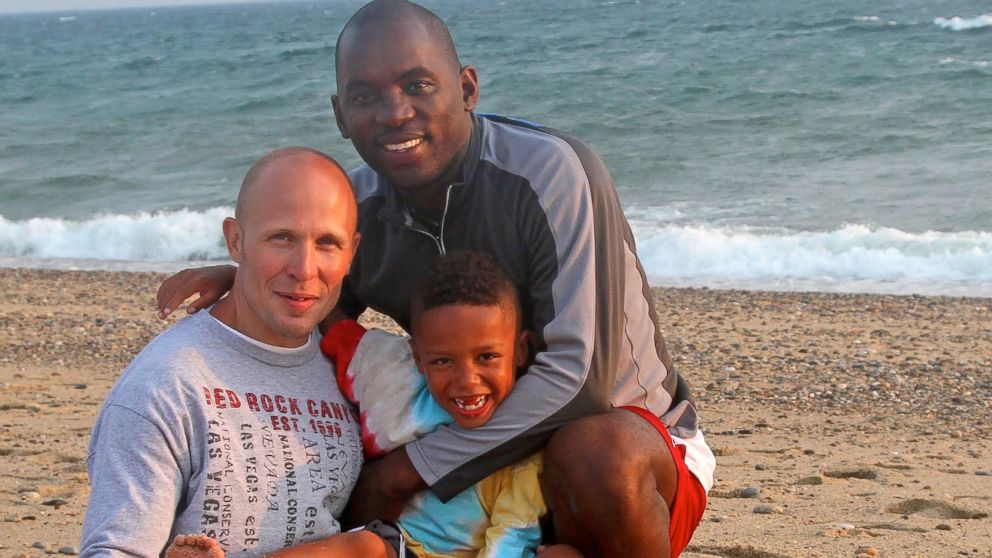

Philip McAdoo and his partner, Sean Cavanaugh, were in the process of adopting their son, Zaden, while living in New York City before same-sex marriage was legalized there in 2011.

But by the time the official papers were finalized last year, they had moved to Georgia where laws prohibit gay marriage and adoption.

Philip and Sean with their son, Zaden

“During that whole period, we were being watched and observed before the adoption was finalized,” said McAdoo, a 42-year-old doctoral student in education. “All that period we were considered a family, but only one of us was allowed to adopt him.”

Zaden, now 8, was a foster child, in desperate need of a family.

30 States Ban Second Parent Adoption

Today, an estimated 399,546 children remain in foster care in the United States, according to 2012 statistics from the U.S. Administration for Children and Families . Of those, 101,719 are waiting to be adopted and 23,439 have “aged out” of the system.

“We wanted a black boy because they are considered the hardest to adopt and most at risk,” McAdoo said.

California Considers Multiple Legal Parents

In Georgia, where the couple moved because Cavanaugh works for the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 7,669 children are in foster care and 1,645 of them are waiting for homes, according Allies for Adoption, a campaign to allow adoption by lesbian, bisexual, gay and transgender couples in all 50 states.

Its public education campaign is sponsored by the Family Equality Council, a national organization that advocates for LGBT parents and their children .

They say, too, that many potentially good parents are being overlooked. The majority of states do not allow adoption by same-sex couples.

Visit Equally Family, Equally Wed’s dedicated site for all families.

“Right now there are children waiting to find a forever family, and until we knock down barriers to adoption by LGBT people in every state, we are failing them as a nation,” said Gabriel Blau, executive director of the Family Equality Council.

Same-sex couples with children are four times more likely than their heterosexual couples to be raising an adopted child and six times more likely to be raising foster children, according to research from the Williams Institute , an LGBT think tank at UCLA.

Yet only 19 states and the District of Columbia permit same-sex couples to adopt jointly ; only 13 states and D.C. allow second-parent adoptions; and only six states explicitly ban discrimination based on sexual orientation in foster care. But Focus on the Family , a Christian ministry that is dedicated to helping parents raise children according to biblical principles, said the push to legalize same-sex adoption has a “fundamental flaw.”

“The ideal in the foster care system is to give children what they don’t have — a forever loving home with both a mother and a father,” spokesman Paul Batura wrote in a statement to ABC News. “But by its very nature, same-sex parenting deprives a child of a mother or a father.

“We believe an adopted child has as much right as any other child to be raised in the environment most likely to promote, preserve and protect his or her emotional, psychological and physical well-being — in other words, with a married mother and father.”

In 2013, the Supreme Court dismantled the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), giving same-sex couples who are married the same federal rights as their heterosexual counterparts. But the states still have a patchwork of laws regarding marriage, adoption, taxes and inheritance laws.

Through a loophole in the law, McAdoo and Cavanaugh were allowed to adopt Zaden in a small Georgia county where one rotating judge interprets the law more liberally. But Zaden only has one parent on his birth certificate.

“We were flabbergasted,” McAdoo said. “His birth certificate will follow him for the rest of his life and only one of us is acknowledged. I am on it, but my partner is not. … I wonder what it will mean and what kind of hurdles there are.”

According to a variety of studies, children raised in LGBT families fare as well as in hetersexual families.

“The research is unequivocal that lesbians and gays make good parents,” said Adam Pertman, president of the Donaldson Adoption Institute and author of “Adoption Nation.”

“It doesn’t mean they do any more than straight parents, but when kids need homes, there is zero reason not to do this.

“Laws that are implicitly or explicitly aimed at adults are, in fact, hurting children because they simply eliminate good potential parents,” he said. “If children are our primary focus, then we should be taking steps to include more and more adults to include, rather than exclude.”

An estimated 6 million children are being raised in the United States by a least one LGBT parent , according to the Williams Institute.

Find more resources for LGBT parents adopting.

In states like Michigan, there is a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage, as well as an explicit on one adoption.

Kent Love, director of communications at Michigan State University, and Diego Ramirez, a pilot for Delta Airlines, were legally married in Washington, D.C., and live in Lansing, the Michigan capital. But they have not been allowed to adopt their 3-year-old son, Lucas.

Love, 43, and Ramirez, 34, have been together for 11 years and were subject to a thorough home study. The birth mother selected them from other couples, including straight ones, to raise Lucas in an open adoption, they said.

“Fortunately, we would go to the doctor’s appointments and we were both present at the birth,” Love said. “Diego cut the umbilical cord. It was quite a blessing.”

But only one was legally able to adopt and the couple refuses to say which one. They have jumped through “extra hoops” to ensure the nonlegal parent has guardianship rights, rather than next of kin.

“We have recognition at the federal level, but not the state level,” Love said. “Honestly, the biggest fear is a situation I hate to imagine: If we were divorced or separated, the nonlegal parent would have no rights.”

Pat Silverthorn, a 53-year-old tech specialist in an elementary school, has no legal rights to her 12-year-old son Corey. She and her spouse, Sue Anna Clark, 57, were married in Washington, D.C., and live in Reston, Va., where their marriage and adoption is not recognized.

“We adopted Corey when he was four in New York City, but the adoption couldn’t be finalized right away because there were issues with the birth father and not being able to find him,” Silverthorn said.

Clark, who is Corey’s legal parent, recently retired and no longer has health insurance from her job as a high school teacher. So now, instead of paying $100 a month, she pays $950 a month for Corey’s and her coverage.

Silverthorn, who is working with benefits, cannot include their son because she is not the legal parent.

“In Virginia, they have done everything they can to put obstacles in our way,” she said.

Even if the couple moved across the river to Washington, D.C., where gay marriage is legal, Silverthorn still would not be able to include Corey on her health policy , because she works in Virginia.

“We have a right to live in Virginia and to continue to live here,” she said. “We know many, many couples like ours. In our world, our neighbors and in school soccer clubs we are just parents — like everyone else.

“We have never encountered a neighbor or a co-worker or teacher who has been anything other than treat us like a family.” —Susan Donaldson James for ABCNews.com

This article originally appeared on ABCNews.com and is republished on EquallyWed.com with written permission.

Photo courtesy of Philip McAdoo

MOST VIEWED STORIES

- Lemon party inspiration from Engage!25 Santa Barbara

- Your 2026 Wedding Planning Playbook: Decoded from the Year’s Trending Google Searches

- Supreme Court Declines to Hear Marriage Equality Case

- From Swipe to Soulmates: How Daniel & Michael Found Love After a Life-Changing Spinal Cord Injury

- Brighten Your Smile: 5 Teeth Whitening Options for Your Engagement Photos and Wedding Day