Fashion-forward lesbians are turning to the gentlemanly tradition of bespoke suits.

Over the last five years, the bespoke suit industry has gained a cult following from fashionably clad lads fed up with off-the-rack labels, and now, the market’s couture umbrella is opening to more and more women, in particular, those who prefer a dash of masculinity into their wardrobe.

However, as women enter the tailors’ shops filled with their chalk-dusted patterns, the bespoke jargon and intimate, often unapologetic appraisal of the body can be intimidating.

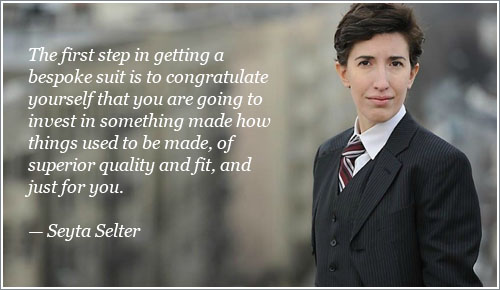

“The first step in getting a bespoke suit is to congratulate yourself that you are going to invest in something made how things used to be made, of superior quality and fit, and just for you,” says Seyta Selter, owner of Duchess Clothier, which specializes in custom suits for butch brides.

As with any aspect of your upcoming wedding, you want to feel comfortable and assured that the vendor is creating a craftsmanship that you and your soon-to-be wife will be completely enamored by, all the while relaying your desire for a strong, structured suit as opposed to one that hugs the feminine form.

| While your tailor should thoroughly explain every detail, here’s a quick vocab lesson in bespoke terminology:

Break: The break is the fold that happens with lengthier trousers where they touch the shoe. Cuff: A turned up hem, as found at the bottom of the leg of trousers or at end of shirt sleeves. Cummerbund: A broad waist sash, usually pleated, which is often worn with a black tie. Cut-Away Collar: Style of shirt collar that is more cutaway towards the shoulder, in varying degrees. Also referred to as Windsor collar. Drape: The way a fabric hangs in folds. Double-Breasted: Can be worn in place of the single-breasted in most situations. It is considered less formal, but that formality is more of an anachronism these days. It can be worn with a stiff front and wing collar, or a soft, turn-down collar. No waistcoat is ever necessary with a double-breasted jacket. French Cuff: Style of cuff on a dress or formal shirt, which is folded back and then closed with cufflinks rather than buttons. Also known as double cuffs. Gorge: Refers to the depth of the where the first button of the jacket or vest lands. For busty women, it is usually most flattering to have the gorge land either mid-chest right at the bustline, or a few inches below. Handle: The feel of textiles when handled. Interlinings: Jacketing lining made of a variety of fibers depending on usage and weight, often Bemberg, pure silk, twill, satin, rayon or viscose. Lapels: Commonly known as the collar, a notch lapel is triangular in shape (and most common), while a peak lapel is v-shaped that points upward and a shawl is rounded (least formal). Linen: Natural vegetable-based fiber, often seen in spring or summer styled suits. Luster: Term used to describe the intensity with which light shines on a piece of fiber. Made-to-Measure: Garment made from a pre-existing stock pattern that is altered, usually by machine, to fit the customer’s measurements. Melton: Felt-like cloth used to complete the under collar on a jacket or coat. Merino Wool: Fine, silky and super soft, it is the finest grade of commercial sheep’s wool available. Mohair: Luxurious, lustrous and durable fiber produced by Angora goats. Pleat: Fold of fabric generally pressed flat to allow extra room in the garment. Puckering: Tendency of cloth to gather in runs, often apparent on the lapel and trouser seams and most common in fused apparel. Single Cuff: Cuff normally found on business and long sleeve casual shirts. Sleeve Pitch: Angle at which the sleeve is pitched to the sleeve head. In a bespoke suit the sleeve is pitched to match the angle at which the arm hangs naturally from the shoulder. Taper: To become narrower, as in a trouser leg that is narrower at the ankle than the knee. Tweed: Rough twilled woolen weaves and cloths used for suits, jackets and overcoats originally produced in Scotland. Twill: Strong, woven fabric characterized by a diagonal weave. Vents: Slits in the fabric either in center or side, based on preference. |

Q&As

The terms you use when describing your vision play a huge role in it becoming a reality. “Definitely ask if they have made masculine suits for women before,” explains Selter. “A good way to phrase this is to say you are looking for a ‘masculine silhouette.’ If they haven’t, or seem uncomfortable or confused, turn around and walk out the door.”

Another good rule of thumb for brides wanting a handsome fit is to steer tailors away from princess seams. “These are the vertical seams you see on a lot of ladies’ garments that give them an hourglass shape,” she adds.

Also ask about what the fitting process is like, and what they guarantee with fit. Since this outfit is an investment, nothing less than hand-stitched heaven, you want to make sure that if it isn’t exactly as you want it when it is complete, that they are committed to fitting it on you properly.

Photo: Jessica Watson Photography

Dress the Part

The best way to give your tailor a true reflection of you is to dress like you. “Don’t try to dress up for the tailor,” says Selter. “Wear clothing that is as you as possible.” The tailor may request what they would like you to wear, most often to get an idea of how you prefer your pants fitted, and if this is the case, be sure to wear your favorite pair, whether they be hip-huggers, high-waisters or skinny jeans. “Your personal style coming into the consultation should alert the tailor of what you might like, in addition to what you verbally communicate to them.”

Selter also recommends wearing the undergarments (or something similar) that you’ll be wearing on the big day when you go in for your measurements. If you bind your chest, or plan on doing so for your upcoming wedding, be sure to do the same when you get fitted. “Breasts can vary in size so much from undergarment to undergarment, especially if binding is involved,” she explains. The same with the bottom half, whether you prefer loose boxers, briefs or anything in between, wear the pair you prefer.

The Process

Three months before the big day, mark on your calendar to start the bespoke suit process, starting with a consultation and ending in what is hopefully your dream suit.

“At Duchess, expect a really fun meeting where we get to find out about your event, your tastes, your fit likes and dislikes and then dive into books and books of swatches,” she says. “Each meeting is different, depending on how much the client knows what they are looking for, and what they have already thought about.” Regardless if you’re well-versed in suit lingo or a bespoke novice, your tailor should thoroughly explain each step in detail as you wind through style, fabric and detail decisions. “Different tailors have different methods of working with styles and details—some have books of style drawings; others have photos of details such as pocket styles to choose from,” she explains. “We have made our process friendly to both generalists, who aren’t sure what they want, and detail-oriented people, who want to choose every style element separately.”

During the first fitting, you can expect about 30-40 intimate measurements taken of your body in order to ensure you receive a custom suit that is flawlessly fitted. Once style preferences have been voiced and measurements taken, the tailor then stitches a suit to baste stage, which is a suit temporarily stitched together so it can easily be taken apart for alterations. Your baste fitting will take place approximately 4-6 weeks after the first, at which your tailor, armed with chalk, pins and a measuring tape, will make adjustments. Afterwards, 80 rigorous hours of labor are put forth toward your custom creation. Once the suit is completed, you’ll go in for one final fitting and approval.

Then it’s time to take one well-dressed step toward forever.