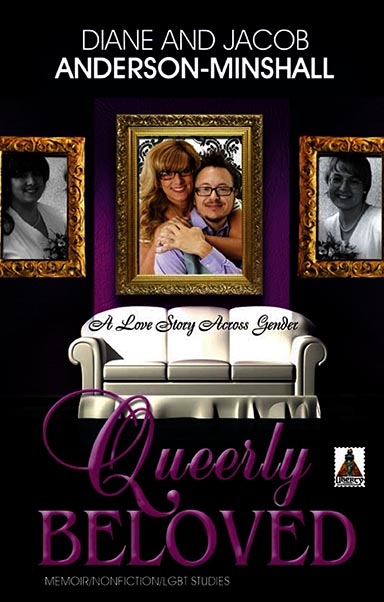

Queerly Beloved: Surviving Gender Transition, Multiple Weddings, and the Fight for Marriage Equality

My wife and I have been married four times. In our 23 years together, we have taken every opportunity to obtain even the smallest sliver of recognition for our relationship. In our first year together, back when Diane and I were both 22-year-old baby dykes, we drove from Pocatello, Idaho, to West Hollywood, Calif.,—during the winter in a VW bus with no heat—to sign the city’s domestic partner registry; even though it granted us no additional rights or responsibilities.

We signed with the city of San Francisco the first year it established a domestic partnership registry and we were some of the first couples to do so again when the California state version premiered.

In March 1996, Willie Brown, then-mayor of San Francisco, invited Diane and me to a same-sex wedding of about 150 couples. The event was merely symbolic, but we saw it as both an opportunity for queer activism and our chance at the most official wedding that we’d ever had.

We embraced the chance to create the wedding of our dreams—that is, our dreams metered by our financial reality as underpaid co-founders of the lesbian magazine Girlfriends. We did our wedding registry at Target, bought our wedding cake at Albertsons and found matching wedding dresses at Ross Dress for Less.

Being butch-identified, I’d never really dreamt of wearing a gown, but Diane convinced me that doing so would improve our chances of being interviewed by the mainstream media. As we suspected, dozens of cameramen were on the scene to witness the highly publicized event. And they did seem particularly drawn to the two brides in matching gowns. We were able to give well-rehearsed marriage equality sound bites, which later appeared on TV news broadcasts around the country.

If there had been any doubt before, from that point on Diane and I felt married. After all, we had the wedding photos and a certificate, and even a wedding announcement in the local (mainstream) newspaper to prove it. We also legally changed our names, each taking on the hyphenated last name Anderson-Minshall and began to introduce each other as “my wife.”

In the 1990s, this seemed like the best we could ever hope for as a same-sex couple. We were registered domestic partners, had been fortunate to have had a wedding ceremony and smart enough to sign reams of legal documents—like durable power of attorney, power of attorney for health care, and living wills—to ensure that we had as many of rights straight married couples did as we could.

Then, on Valentine’s Day in 2004, we were stunned to learn that San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsome had directed the city to issue same-sex marriage licenses. We rushed to city hall and joined dozens of other gay and lesbian couples hoping to marry. The line wound out of the building and it took something like five hours before we made it to front and were granted a license to wed.

Since none of us, not the couples in line or the city officials or the activists, knew how long this legal window would be open, no one wanted to leave the building without taking the next step. Fortunately, as word spread, a handful of religious leaders and justices of the peace made their way to the city hall, offering instant weddings.

We served as witnesses for the couple in front of us, and the couple behind us did the same for us. We stood at the bottom of the city hall’s grand staircase and said, “I do,” to each other, then hurried to another line, desperate to complete the steps needed to have our marriage legally recognized before the clock struck 5.

We left city hall that day with official documentation of our marriage. And for a few months, as court battles raged in the state, it seemed like we might be allowed to keep it. Instead, we received an apologetic letter from the city of San Francisco informing us that our marriage—along with all the others filed by same-sex couples that February—had been invalidated. It was a cruel reminder of our second-class citizenship.

Everything changed for us in March 2006.

Since 2004, I had come out as a trans guy, changed my name, started testosterone therapy, undergone surgery and had my gender officially changed on my California ID. Now that I’d become a man in the eyes of the law (at least in California), Diane and I had suddenly won the right to legally wed.

The other couples who had joined us at city hall still had years of propositions and court battles ahead before they would earn the same privilege; which made us wonder if we should go ahead. But with the support of our friends and fellow marriage equality activists, we did.

From the beginning this wedding was different. It wasn’t about rights or politics, it was just about us and our commitment to each other, but it was quickly apparent it would also be the first one to be accepted by mainstream society as “real.” It didn’t seem to matter that we’d been together 16 years, combined our finances and households and participated in multiple ceremonies; the day after this wedding was the first time many straight people truly viewed us as married.

This time we didn’t invite members of the press but we did invite our family members; and they surprised us by sending in their RSVPs right away, so we incorporated them into the wedding ceremony. My mom read a passage from the Bible, our sisters were bridesmaids, Diane’s brother a best man, and her niece and nephew served as the ring bearer and flower girl.  Strangers treated us differently, too. When we were filling out wedding registries, purchasing wedding rings, having Diane’s designer-knockoff dress made and renting my tux, sales people, clerks and other customers ooohed and ahhhed about our upcoming nuptials.

Strangers treated us differently, too. When we were filling out wedding registries, purchasing wedding rings, having Diane’s designer-knockoff dress made and renting my tux, sales people, clerks and other customers ooohed and ahhhed about our upcoming nuptials.

Afterward Diane discovered that simply substituting the word “husband” for “wife” was like a magic key that gave her unfettered access to my personal accounts and medical records. In small, barely perceptible ways throughout the day, our relationship was acknowledged and respected the moment we were seen as both an opposite-sex couple and “really” married.

Although we hadn’t courted the media at the time of our last marriage, a later interview about our Blind Eye mystery series led to an article in Catholic Daily News that suggested I had actually transitioned just to get married. The writer worried that other gays and lesbians would rush to this “loophole” and undergo a gender transition to get around the laws prohibiting same-sex marriage.

Of course that never happened. Instead, same-sex couples just kept fighting for their rights, activists kept pursuing court cases, queer media kept increasing our visibility, and thousands of LGBTQ individuals came out and demonstrated how similar straight love and queer love can be. Thankfully, all the hard work has paid off and the tide against marriage equality has finally turned.

Our personal story to marriage equality is now just one of hundreds, but we’re still honored that we were able to play a small role in this historical social change.

Jacob Anderson-Minshall and his co-conspirator Diane (currently editor-in-chief of HIV-Plus magazine) are co-authors of the 2014 memoir Queerly Beloved: A Love Story Across Genders.